It’s my last day with Khouloud and Jamal and I’m struggling with a decision. Whenever possible I like to take a print back to give to those I’ve documented, and in my bag I have a photograph I took of the couple two years before. But should I give it to them?

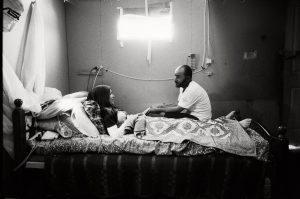

In the picture Khouloud, paralysed from the neck down, lies in the tent she shares with her family in Lebanon’s Bekaa valley. Jamal sits at the end of her bed, holding her hand, the couple looking at each other with a love that is at odds with the stark, grainy black-and-white image that reflects the truth of their desperate situation.

If there is one image that betrays my belief in the power of photography to create change, it’s this one. For here we are, two years later, sitting in that same dark oppressive tent and nothing has changed. Naively perhaps, I’d believed that telling Khouloud’s story would have made a difference, and I can’t help feeling I failed them.

Finally, I reach down and take the photograph out of my bag.

As I hand it to them I say: “When I took this two years ago, I didn’t take a photograph of a refugee, I didn’t take a photograph of a disabled woman; instead I took a photograph of a couple who are deeply in love, and that’s what this will always mean to me.”

In 2014 I went to Lebanon with Handicap International to document some of Syria’s most vulnerable refugees. The sick, the elderly, single-parent families and those living with disabilities. People like 38-year-old Reem. She was in bed at home in Idlib, Syria, when a rocket hit her house. Her husband was killed next to her, one of her children also died, and Reem lost a leg. When I met her she was living in a tent on the top floor of an unfinished building. She was still learning to use her prosthesis and was unable to use the stairs, leaving her trapped. She didn’t want her surviving children to live with her – she felt ashamed because she believed her disability meant she couldn’t be a mother to them.

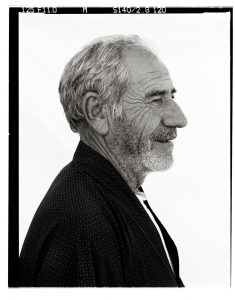

Only her father, Abdel, lived with her on the rooftop. As I was taking his photograph, Abdel kept looking to the side, his eyes focused on the distant snow-capped mountains. I asked why he kept looking that way.

“Those mountains,” he replied, “are my home. I am an old man and may never return home, but at least each morning it’s the first thing I see, and when I go to bed the last.”

For the full story visit The Guardian